News Letter II

Landless Workers; Trumponomics; Spanish cover

I have a big (long) cover story in this month’s edition of The Nation, on Brazil’s much-beloved Landless Workers’ Movement (MST). It is now online, here. It is long.

Speaking of Brazil, President Donald Trump’s tariff misadventures reminded me of a story from 2018.

After winning the presidential election, Jair Bolsonaro announced that he would abolish the Ministry of Environment. You see, he believed that if you simply got rid of the do-gooder, politically correct tree-hugger (gay) leftist bureaucrats, there were untold wonders to be harvested in the Amazon. Brazil was being screwed, and if you just opened up the country for exploitation, you could basically walk into the forest and pick gold coins off the ground.

What happened? Major representatives from Brazilian agribusiness — that is, the most important faction of national capital — told him to please keep the Ministry. You see, the country was already being exploited. Brazilian agribusiness was doing very well, carefully inserted as it was into a global network of markets, regulations, and corporate greenwashing initiatives. Destroying the Ministry would simply make it harder for them to sell their products abroad.

Reading the Financial Times over the last few weeks as commentators and analysts tried to understand what the United States is doing to the global economic system that it constructed, something remarkable became clear. Trump’s particular trade war only makes sense if he actually believes that the US is being screwed by the rest of the world. He truly thinks that we are getting played, because we buy things from other countries, and they get to keep the money. Trump reckons he has discovered One Weird Trick to win at global economy — just bully everyone! Well, everyone else knows how much bullying already went into building a global capitalist system with the United States as its hegemonic power; the country sits atop a carefully constructed world order that provides great benefits to the US American ruling class.

This aggrieved insistence that there are easy solutions to everything is a hallmark of the anti-political insurgency that has driven world history for fifteen to twenty years. Its ideological ne plus ultra may be: “these politicians are such clowns that a literal clown would do a better job.” (I tell this story in my second book.) I wonder how much of the hidden infrastructure of US empire this clown is going to destroy before he is finished.The nice people at Capitán Swing in Madrid will be publishing the Spanish-language edition of If We Burn on May 19. Here’s the cover:

Back to the MST story. I began working on it in 2023, and it covers a period from roughly 2017 to 2025 in the history of the organization. So I don’t think it matters too much that I am two weeks late in sending this out; it is the kind of thing that you can read whenever you have time (it is long).

I did conceive of the article, in a way, as a follow-up to If We Burn. I will explain that a little bit now, so feel free to stop here if you didn’t read that book. At the end of this post I’m including some links (mostly in Portuguese) for those that want to learn even more about the MST.My editors cut a couple of paragraphs from the conclusion to If We Burn that discussed the MST in relation to the Movimento Passe Livre (MPL). They were right to do so; it was too much new stuff to introduce too late in the game. The book focuses on actors that change during the decade; those that move from horizontalism to a kind of post-horizontalism, or from a belief that spontaneity and structurelessness are inherently positive to an appreciation of coordination and structure, and so on; we also speak to horizontalists and anarchists who stick to their guns; but the book does not spend a lot of time on the groups (like the MST, or PCdoB, or KPU) that never believed in those types of explosive mass protests in the first place. I figured they weren’t really part of the main story in a book about these revolts; but they were there.

Three things are worth mentioning in this context. First, the MST knew the MPL back from the days of the “Veggiefest” punk shows. In June 2013, the MST told the MPL to negotiate with the government and offered to intermediate. The MST leadership told me that they, obviously, employ protest and direct action to pressure the government, but are wary of unpredictable explosions that can amount to destabilization.1 Secondly, as its members are proud of pointing out, in the dark years of reaction in Brazil (2015 to 2022) it was well-structured groups like the MST that stepped up to oppose Lula’s imprisonment and to provide emergency assistance to starving Brazilians (the piece covers much of this). No apparently spontaneous, digitally coordinated uprising appeared to stop Bolsonaro.2 It was the Workers’ Party, and unions, and social movements, and the rest of civil society, they say, that (barely) constructed an effective frente ampla, a broad-based pro-democratic united front, in 2022.

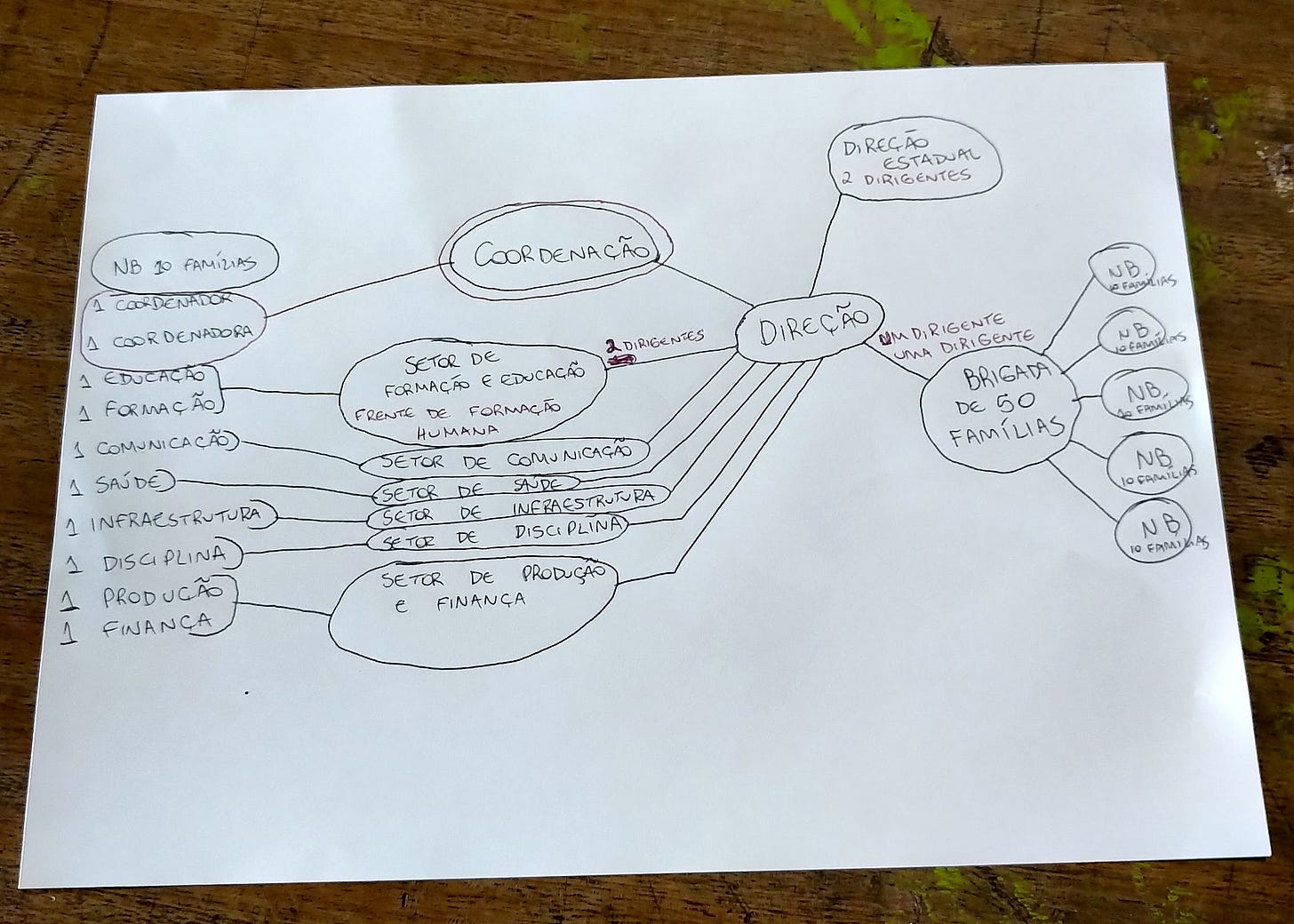

And third: the MST manages to thread the needle through a number of very tricky dyads. They combine approaches that are sometimes seen as diametrically opposed, resolving apparent contradictions (or, if you like: staring these organizational contradictions squarely in the face, realizing that they cannot simply be wished away).They have clear leadership, but it is collective; they have a long-term, revolutionary project, but put food on the table for working-class Brazilians every day; they are a mass social movement that reads Lenin; they aim to make decisions through consensus at the local level, but employ democratic centralism on the big questions (Neuri Rossetto told me they employ a “hybrid mode between democratic centralism and decentralization”)3; they have a big, complicated hierarchy, but are relatively porous at the margins; they consider internal discipline to be paramount, but have any easygoing relationship with the rest of civil society; they fought to get Lula elected, but do not fall in line behind governments they support; they are both pragmatic and fiercely anti-imperialist; they organize both vertically and horizontally, etc. I think all of that is interesting, even if we set aside the question of land reform in Brazil (or the relevance of that focus outside the country).

***

More on the MST:

Movimento Dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (official page)

The Political Organisation of Brazil’s MST - Tricontinental (English)

Brava Gente, a very long interview with João Pedro Stédile (1999)

A bit of the conversation with Neuri Rossetto did make it into the Portuguese-language version of the book, as a late footnote, since the MST requires no explaining in Brazil.

Of course, I participated in the “Ele Não” protests, which served an important role for galvanizing resistance, but they didn’t really get in Bolsonaro’s way on their own.

“No MST há um modo híbrido entre um centralismo democrático e uma descentralização nas decisões políticas e organizativas. A estrutura organizativa é centralizada e vale para todos os estados. As ações nacionais também são tomadas pela Direção Nacional que conta com representantes de todos os estados e setores organizados. Essas são as jornadas nacionais, realizadas conjuntamente no mesmo período do calendário. Por último, estão centralizadas as Relações Internacionais, que fica sob responsabilidade de um setor específico, sob coordenação da Direção Nacional.

Por outro lado, há uma descentralização na escolha das formas de lutas, na escolha das áreas reivindicadas para a Reforma Agrária, em outras atividades de lutas e ações políticas (para além das jornadas nacionais), nas relações políticas em cada estado, na criação dos setores organizativos, na definição das atividades produtivas e econômicas, etc.”

This was an excellent article, both from a historical and organizational perspective. Do I see a book in the future on the topic?

By the way, there is a very good movie about Dr. Nise da Silveira, with Gloria Pires, entitled "Nise: O Coração da Loucura" (2015).

I like that the Spanish title can be read as "Yes, we burn"