I'm still here

Ainda Estou Aqui (I’m Still Here) — Directed by Walter Salles, 2024

If you set a film in early 1970s Brazil, you have an excuse to use some of the best songs of all time. If the action takes place in Ipanema, you can point the camera at some of the most stunning beauty surrounding any city ever built. If you tell a story from the point of view of a sweet young boy, looking back on a time of bliss that was taken away from him, you can fill the screen with euphoric and exuberant love, and exclude the kinds of inevitable domestic problems that he may not have noticed, or may have scrubbed from his memory in the years after the tragedy.

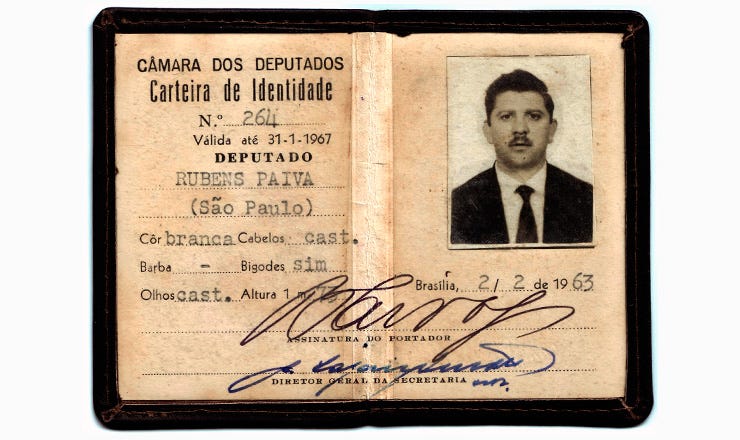

And if your subject is the family of democratically elected congressman Rubens Paiva, you can dispense with difficult moral questions, since your protagonists are unambiguously and canonically innocent.

I went to the cinema the other day in São Paulo. I was ready to roll my eyes at a billionaire director re-telling the only story that Brazil’s elite center-left ever seems to tell about the dictatorship. Instead, I found them flooded with tears. Rubens Paiva is one of the most famous victims of the military regime, and his family heroically fought for his memory after the generals took him away. In less capable hands, Ainda Estou Aqui could have been an exercise in cheap point-scoring for the pro-democracy crowd (admittedly, we could use the points) in a moment of global authoritarian retrenchment. Instead, they made a deeply beautiful film that bathes luxuriously in its simplicity and its purity. After the film, I sat there stunned until the end of the credits. (For what it’s worth, I saw it on Rua Augusta, just down the road from the bar where they snatched Dilma Rousseff, back when she actually was part of the armed resistance to the dictatorship). I will be spending more money to see it again in the theater, and suggest you do the same.

I would venture to say that the movie is not really political at all, unless a breathtaking painting of Christ on the cross is a theology text. All you need to know is that a US-backed right-wing dictatorship snatches a man from his home, tortures him to death, and leaves his family to flail in the aftermath. They must deal not only with his disappearance, but with the fact that the military regime has made up a nonsense story that he was freed from captivity by Marxist guerrillas, refusing to admit they killed him and thus making him into a desaparecido.

But — and this is the heart of the film — his wife Eunice does not flail. “I’m Still Here” is a masterful and truly moving depiction of happiness in a large family and strength in a single woman. Personally I don’t care much about acting. But thinking back on the performance delivered by Fernanda Torres, I start to tear up once more. The depth of emotion in her face provides all the nuance any film could need. This is a movie about quiet determination and the celebration of life, not the politics of the Cold War in the Global South. But since the latter is my thing, I will try to offer some context.

The Brazilian dictatorship did not begin, like its counterparts in Chile or Indonesia or Argentina, with a homicidal purge of the left from the body politic. After the 1964 coup, quite a few people in the political establishment, including deposed president João “Jango” Goulart, thought things might soon return to normal.

Jango took power in 1961, with fractured support in the political establishment and a plan to implement moderate reforms. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy told his ambassador to prepare the ground for a possible military coup. Jango was certainly no Marxist revolutionary — at best, he was a liberal reformist who wanted to extend the right to vote to poor and black Brazilians excluded from the franchise, and put forth a moderate land reform program. But these changes posed a real, if relatively small, challenge to the privileges of the ruling class. Brazil’s O Globo newspaper implied the national literacy program was a secret Communist plot.

In 1964, the coup went off without a hitch. With “Operation Brother Sam,” the Lyndon Baines Johnson administration secretly made tankers, ammunition, and aircraft carriers available to the golpistas. None of that was needed, since the putsch was supported by so much of the country’s establishment, along with nearly all of its media.

In its first “Institutional Act,” the junta nullified the positions of a number of democratically elected lawmakers. That included Rubens Paiva, a member of Jango’s Brazilian Labor Party (PTB) who, like the ousted president, hailed from Brazil’s landowning elite. Paiva fled to Europe. But soon, he came home. It seemed that he could set formal politics aside, return to work as an engineer, and live peacefully in Rio de Janeiro. As the film demonstrates with chilling patience, he was wrong.

The years of lead, the anos de chumbo, began in 1968 as the regime unleashed a fifth “Institutional Act” (AI-5) and cracked down on a small guerrilla movement. Someone like Rubens Paiva, who remained in contact with the exile community, could be swept up in the repression. This would not be a short break from democracy. In the eyes of the US Ambassador Lincoln Gordon, the coup had stopped Brazil from becoming “the China of the 1960s” and would serve as a model for Chile a few years later. Brazil’s dictatorship would last until the end of the 1980s, and it would take another two decades to reveal the truth of what happened to Rubens Paiva.

In 2012, I interviewed his daughter, Vera, as well as Caetano Veloso, (who is also heavily featured in the film, graças a deus) as Dilma Rousseff’s government unveiled the findings of the Truth Commission. They were still fighting to get the military to admit they had lied. That piece of closure came in 2014, and Marcelo Rubens Paiva published the book about his parents, Ainda Estou Aqui, in 2015.

Brazil’s military dictatorship colonized the Amazon, wrought death and destruction on its indigenous peoples, and — this was the major point — preserved the structure of the wildly unequal society that Jango’s reforms (and more radically, the left) sought to reorganize. But as a macabre numbers game, when it comes to the direct murders of its perceived political opponents, the regime disappeared less people than Argentina, Chile, or Guatemala. Rubens Paiva was taken away in 1971. A few years later, the death of another well-connected citizen, Vladimir Herzog, helped galvanize the process that culminated in democratization.

For pro-democracy and left-of-center Brazilians, the stories of Paiva and Herzog are about as well-known and important as Pearl Harbor is to patriots in the United States. In 2018, I wrote about the 1964 coup and the first “Institutional Act” in an essay for the New York Review of Books, in which I warned that extreme-right president Jair Bolsonaro would try to carry out a coup of his own. I wrote about the murder of Vladimir Herzog, and its repercussions for the dictatorship, in my first book, The Jakarta Method.

Fifteen years ago, there was perhaps no political truth more universally acknowledged in Brazil than Rubens Paiva and Vladimir Herzog did not deserve to die. This assertion undergirds the transition to democracy and the establishment of the 1988 Constitution. If you asked the high command of the Armed Forces themselves, they would have agreed with this interpretation. So then, why is there a need to re-assert it now, as Salles does with this film?

The hegemony of that assertion, the fact that it became a nearly universal truth for the political establishment, is a big part of the origin story of Bolsonaro, who grew up near property owned by the Paiva family. As the story goes, he seethed with rage at the privileges enjoyed by a wealthy clan that he believed had conspired against the fatherland. He despised the “politically correct” civil society that united in holding these men up as martyrs. In 2014, he spit on a bust of Rubens Paiva unveiled in Rio de Janeiro. In 2016, he declared war on the entire political edifice by dedicating his vote for Rousseff’s impeachment to her torturer. An unthinkable thought — they deserved it — entered the mainstream.

On the one hand, Ainda Estou Aqui plays it safe. There is arguably more complex terrain to explore, such as the social consequences of the dictatorship outside elite urban circles, or the thorny questions of the ethics and strategies of resistance under authoritarianism. In the film, the question of class is basically absent, except for one moment in which the family maid politely indicates she has not been paid since Rubens disappeared, and another in which Eunice breaks the news to the kids that they have to move out of their giant house. But it is how they play on this terrain that is so powerful. The execution is magisterial, and this matters both aesthetically and politically.

The film and its well-deserved success place Brazil’s dominant culture industry squarely on the side of opposition to Bolsonaro’s reactionary counter-revolution, just as cultural elites in the U.S. flirt with a “vibe shift” after Trump’s election. As the events of 1964 (and 2014-2018) demonstrate, the well-heeled Globo set can really go either way on these kinds of things.

A friend said, half-jokingly, that she hoped the film might launch a new genre, that it could inaugurate a Brazilian tradition of creating a new anti-dictatorship film every year, in the way the US seems to make a movie about World War II every month. If the film continues to win major awards in Hollywood, as it should, it will do the work of forcing the anglophone culture industry to pay homage to a man (and a movement) the US government helped to kill, whether anyone in the United States knows the history or not.

Thanks, I needed to read this today.

thanks Vincent I see it's playing in my part of the bay area so off we go to the flix this evening