Art in the Age of Claudia Sheinbaum

It is an unfortunate fact that humanity is living through the content-ification of nearly everything. Until relatively recently, we might argue, “content” did not exist at all. But now: politics, art, journalism, culture and life itself is content, too. We feel this here in Mexico, of course. Indeed, we may feel it more intensely, and in a unique way, as a result of our special relationship to the country north of the border. The process of content-ification is intrinsically related to the power of the United States, its inescapable media production, and the internet that its firms control.

As the famous national lament puts it: Mexico suffers because it is “so far from God, and so close to the United States.” And yet, it is perhaps that knotty relationship that has created a special place for us in this strange new global system. In some ways, Mexico appears to be an exception to some of its rules, even as reality here seems violently overdetermined by others.

For example, on one hand: bucking a trend in the hemisphere, we have not experienced a shift to the right or the victory of neo-fascism. We can call ourselves lucky to have Claudia Sheinbaum who, for all her faults, is a democratically elected and popular president, with a plausible claim to being left of center and a solid record of standing up to Donald Trump. On the other hand, our opposition has morphed into a formless, uninspired set of culture warriors attempting to replicate their counterparts north of the border by copying fragments of the United States and pasting them into Mexican politics. These are mad oligarchs and influencer psychos raving that Washington should invade Latin America to save it from ourselves, apparently unworried about the obvious contradictions for their own class. They grab at signifiers and the aesthetics of campaigns which seem to have worked elsewhere, railing against trans people, a “stolen” election (in reality, Sheinbaum won more votes than any candidate in recent history), or decry the censorship of their own yapper class that is somehow always imminent.

And, at the same time, it is woefully obvious that daily life in much of the country is shaped by insatiable US American demand for drugs, and by its endless supply of guns.

I work in contemporary art, as a critic and curator, and trying to read and explain trends in my field in relation to the world-system requires confronting another set of contradictions. Most everyone I know in the world of left-leaning cultural workers came out to vote for Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Sheinbaum’s predecessor and the founder of the ruling Morena party, only for him to turn around and call us all “fifí” or posh. While disheartening, one can admit it was a pretty funny move. It was clear we were not—and are not—the focus of Morena’s political project, and we must recognize just how popular that project has been. At the same time, AMLO, Morena, and Sheinbaum’s choice to further cut funding for the arts left a void that is being filled by the private sector. As institutional support for culture slowly deteriorates, international capital has taken center stage in the Mexican art world.

While those working in public museums, reliant on government art grants, or running state-funded cultural spaces have long had to tighten their belts due to cuts imposed by previous governments, some of us held out hope for a left-leaning movement that viewed culture as a plausible defense against influencer slop and the kind of corporate propaganda that can only push us to the right. This has sadly not materialized, and the tradition of cultural workers protesting for basic provisions carries on in the Morena era.

A century ago, the now-famous muralistas reshaped national culture with ample public support. Artists like José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros forged indelible images of national identity and revolutionary spirit before the Mexican Revolution began the oxymoronic process of institutionalization. After the “Ruptura” generation broke with the “Mexican School of Painting,” no group of artists has enjoyed public support in the same way. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, they were persecuted for their leftwing politics during the so-called “Dirty War.” But cuts to the cultural budget did not become really drastic until the victory of the right-wing PAN, in 2000.

Once more, we are in an especially tricky situation. Of course, artists, curators, and writers like me do not want to respond to Sheinbaum on the basis of narrow self-interest – even though many people in the field struggle to get by. But I am also increasingly worried about indirect effects: a competitive professionalization of culture which is deeply conservative.

In the arts, the response to all of this has been schizophrenic. The scene is divided between those that are highly politicized and those that are not at all. One fraction discusses how class shapes the ways that art is produced, consumed, and circulated in the increasingly gentrified city; to be politicized in this sense includes looking into the sources of funding for events and institutions; this group challenges Zionism and imperialism; and you might have guessed by now that this is my tribe. Along with a few friends I run 333, an art criticism magazine, and we are on that side of the spectrum. The other team is perhaps happier: They simply ignore most politics, picking instead at the juicy morsels of art-market gossip. Somewhere in the middle is the new influencer class. They hail the arrival of my worst nightmare: art and commentary that is merely fun, ahistorical, apolitical content; what I see as the antithesis of art, of critique.

It might be naïve to believe that the arts could be a fruitful space for thoughtful critique of the existing order, as well as a bulwark against fire-breathing attacks from the right. But given the danger of the moment, most members of the weakened cultural class are too scared of catching strays from either side. It is safer to avoid any criticism that could be confused with the insanity of the national oligarchy’s attacks on Morena. This traditional owner class— whose most recognizable ideology was, until recently, being anti-poor and vaguely Catholic—has been acting ridiculously, but this does not mean they are not a threat.

I grew up in Veracruz but now I am, of course, based in Mexico City, the principal node in an extremely centralized cultural structure. And as everyone knows, this city has recently been transformed by its special role in the art world. This is not the only international capital to experience this kind of gentrification this century, but it might be the most jarring case.

It used to be easy to predict where gringos could be found in Mexico City. What I referred to as Gringo Season started some time in fall, usually late November, and extended to a few days after Mexico’s art week in early February; then, our city would once more be clear of the telltale loudness and rudeness of a certain kind of visitor by the beginning of March, when weather in New York started to improve. These flows used to be restricted to Condesa, and then also to Colonia Roma. But they spread to Roma Sur, and then Juárez and Cuauhtémoc; more recently, they have flooded San Rafael and Santa María la Ribera, Centro Histórico, Tabacalera, Narvarte, as well as Coyoacán in the south.

But Condesa wasn’t always the stomping grounds of curiously barefoot US Americans. Just a few decades ago, it was abandoned by the middle-class families that had moved into the area in the 1930s, and it was quickly repopulated by a working class that needed homes after the 1985 earthquake. The story of its recent gentrification can be mapped onto NAFTA, the spread of contemporary art, and a few Gen Xers: Right around the signing of the fatefully destructive 1994 “North American Free Trade Agreement,” a handful of upper-class kids discovered contemporary art and its nascent globalizing potential. The entire world was to be re-made in its non-specific non-image, rendered into its many indeterminate but easily recognizable tropes. This was the era of post-conceptual art, and Gabriel Orozco was the first young Mexican contemporary artist to show at MoMA, in 1991. Back in those days he famously rejected the “Mexican Artist” label, preferring a multi-culti, citizen of the world vibe that was very appropriate for the era.

A pair of entrepreneurial kids, Yoshua Okón and Miguel Calderón, both of whom had studied abroad, were looking, in their own telling, to crack the city open and bring in people from the United States and Europe. They set up shop in Condesa, and opened La Panadería (The Bakery), an artist-run space that from 1994 to 2002 hosted innumerable art shows, punk bands, installations and performances, all broadly rebelling against what they perceived as the too-solemn and self-serious art of then-existing galleries and museums. Two of my favorites were Okón’s Cuarto Enchilado (1994), in which the artist painted a room with glue and then powdered it with Takis-red chili; and Dermis (1996) at which the collective SEMEFO showed real tattoos cut off from the skin of corpses at the morgue (the cops shut it down). Okón and Calderón went on to have significant international careers; you can spot Calderón’s early paintings behind Owen Wilson in a few of his scenes in The Royal Tenenbaums, and he just premiered a theater play a few weeks ago. Okón made a few film installations mocking Mexican Nazi-cosplayers and the excesses of the American lower class; he also founded SOMA, a sort of extra-official two-year art program in the city that has hosted some well-respected artists.

But perhaps their most interesting feat was to make Condesa into a desirable location for artists and ambitious entrepreneurs at the turn of the millennium. Many of those artists came from the affluent families that bought property in the area when it was first developed in the ‘20s and ‘30s. During the art boom, their Gen-X heirs promptly became landlords in an area that they themselves worked to make “cool.”

Until she became Mexico’s first woman president, Claudia Sheinbaum was the capital’s Jefa de Gobierno (something like a mayor). As jefa, she faced COVID and the tragedy of an overhead subway line collapsing and killing 22 people. Many have forgotten that she partnered with UNESCO and Airbnb in 2022, to lure digital nomads to the city—right at the peak of the Great Gringo Invasion.

During the pandemic, a handful of American galleries opened branches in Mexico City, only for them to shutter by 2024. By that time many local galleries and project spaces were suffering as well, and most independent spaces that relied on grants (national and international) were disappearing.

The intensity of all this movement has had a profound effect on the young and not-so-young artists and art workers; it has re-wired their subjectivities, making it feel like the only reasonable option is an extreme version of neoliberal professionalization: if you think of your very self as a firm, why would you run an artist’s space when you could open a commercial gallery?

Art has become much more homogeneous, with risk carefully managed. Many artists started painting or using traditional materials like fine woods and bronze, believing that those costly elements will make their market value clear. Color palettes and formats echo each other across a depressed market. Last year, at Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, I was excited to see Manual Intuitivo: No usar saliva ni soplar sobre las piezas, an exhibition curated by Petra, a curatorial collective from a newer generation, showcasing an intergenerational slice of artists. The show was built on an experimental premise: an intuitive manual, opposed to a museum’s conservation manual, was supposed to bring the contours of the curatorial project into focus. That was, sadly, not the case, but beyond any qualms I had with its conceptual failures, I was mostly struck by the acquiescent conformism of the whole ordeal. Not only were there no new readings on current and older art, but the curators locked in on the exact same things as their predecessors, the themes millennials have explored now for a decade, and that were themselves already a kind of hand-me-downs: art meets technology, urban-flavored pictorial experiments, a flair for mysticism, and idealizations of neo-materialisms. I was especially struck by the evident anxiety that presided, as a younger generation sought to perform a specific local professionalism, discarding their better (perhaps more daring) instincts in order to fulfill a predetermined image of what art should look like.

I want to stress that the artists featured are not bad. This generation has the talent to confront the contradictions of our time; but sometimes, they appear to be hobbled by context and curation. Juni Aranda, one of the artists in the show, recently put up Polen, a small exhibition at the city’s orchidarium. With simple, well-deployed gestures, Aranda was able to conjure earnest and genuine connections with viewers.

By characterizing the whole guild as fifí, AMLO cast a self-fulfilling curse: as the budgets and grants are diminished, it is only the wealthy and the well-to-do who can afford to risk choosing such a precarious field. Few can afford to take any formal or discursive risks. As in most parts of the world, the cuts deepened during the pandemic, but AMLO also earmarked 20 percent of the national culture budget and for the remodeling of the Mexico City’s Chapultepec Park, which he bestowed on Gabriel Orozco – an important figure, but definitely not an architect or an urbanist.

Grants were slashed, theaters closed. Some of us were working at state museums at the time, and it was a bloodbath. We were operating with a tiny percentage of the budget that was routine before the pandemic.

Of course, removing public support for the arts makes us more like the United States, and less like prominent neighbors to the South. In the largest country in Latin America, for example, President Lula made the Ministry of Culture central to the face of the first two Workers’ Party administrations, and famously reversed Jair Bolsonaro’s slash-and-burn policy after winning his third election in 2022.

In Mexico, we hoped President Sheinbaum would turn the ship around, but her government justified cuts in 2025 by claiming that the Chapultepec money sink and the Tren Maya were now completed. Meanwhile, the local state museums are in shambles. Galleries are closed for weeks or months because security guards’ checks won’t clear and payments are delayed endlessly, while most of the very young people hired are told to think of this as normal. We can’t help noticing that they spend the budget on PEMEX debt and on the further militarization of the country, or when the real effects of their domestic policies are frequently indistinguishable from the neoliberal spoliation of their predecessors. On the Fourth of July last year, Condesa finally exploded, in anti-gentrification protests so pointedly aimed at gringos that the international press took quick notice.

Luckily for Morena, nobody can stomach the alternative. Sheinbaum’s most prominent enemies are the lunatics who stand in Congress and—speaking English with their revolting papa-en-la-boca whitexican accent—ask for Trump to come “Make México Safe Again.” You can side with the reasonable-sounding Sheinbaum or you can go with the miserable usurer, Ricardo Salinas Pliego, who owns TV Azteca and refuses to pay the 48.3 billion pesos he owes in taxes. That is the billionaire clown that the right-wing is considering running for president after Sheinbaum’s term ends. It is hard not to support her when she called them out like this at the end of last year: “Their vision is money, accumulation, accumulate, accumulate, accumulate wealth on the backs of everyone else.”

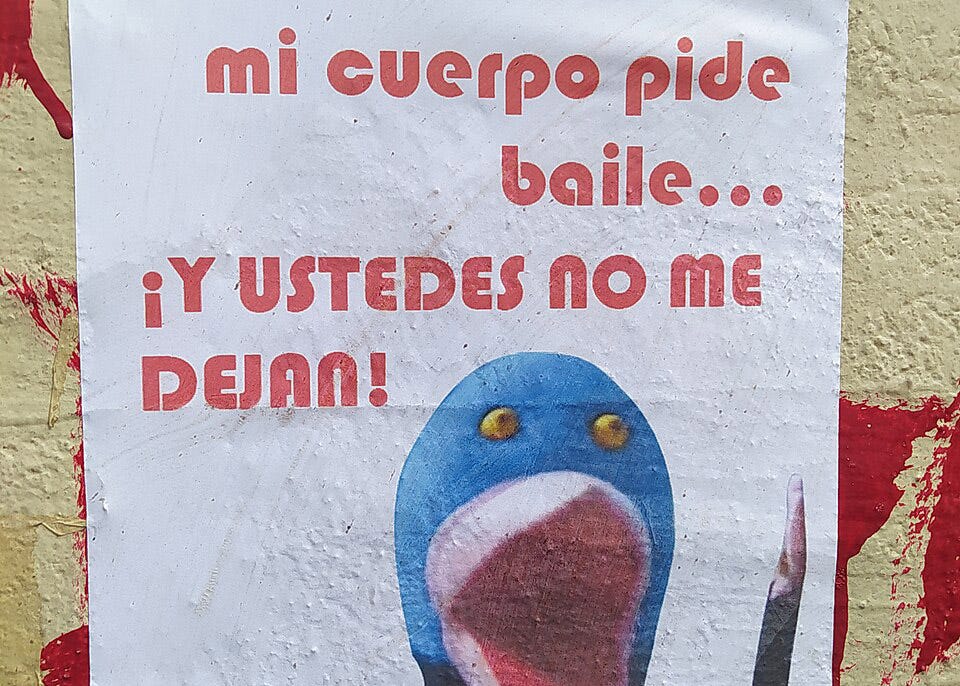

The opposition now also boasts a class of Instagrammable politicians like Sandra Cuevas and Alessandra Rojo de la Vega, both mayors of Cuauhtémoc. The first is a full-blown buchona, who ran the streets in tight black fits and RZR ATVs, while terrorizing the elderly who dared to dance salsa on Sundays in front of her building; the second loves shoulder pads, paranoid rants performed to her front-facing camera, the infinite patting of her own back and making unhinged posts about removing the Che Guevara and Fidel Castro statues installed by the neighbors of Tabacalera in “defiance of dictators everywhere.”

The supporters of all of the above were out in something like ‘full force’ on November 15th for what the media bafflingly called a “Gen-Z” protest: in reality, it was an Astroturfed appropriation of the aesthetics and signifiers of uprisings in places like Nepal, also previously re-enacted in Madagascar and Morocco. Posts with the One Piece logo – the anime symbol first employed in Indonesia last year, before it spread to other protests around the world – popped up all over social media in mid-October; but after Carlos Manzo, an independent mayor in Michoacán, was gunned down in a public Día de Muertos event, Reddit, Twitter and Instagram were flooded with new accounts asking their fellow kids to join in the movement. Some reporting claimed over 8 million bots, mostly from Argentina and Colombia, were heavily promoting the gathering — explaining the frequent slang gaffes.

On the day of the event, the same crowd of boomers and Gen Xers who have been consistently marching every two years since Morena got elected filled up a few blocks of the city they swear is a war-torn, crime-ridden cesspool. Emerging from hysterical Whatsapp groups into the sunlight they screamed: “Trump! Come and get the shit out of Mexico! Come and get Claudia fucking Sheinbaum.”

Like most protests in Mexico City, this one ended in a bit of violence. The feminists and the leftists were promptly teargassed, kettled and beat up by the police. The right-wing aunties were accompanied by a set of thugs of their own, equipped with angle grinders to hack their way into the Palacio de Gobierno. For a moment, it got scary. Alex Jones was tweeting “Mexico Is Full Revolt Against The Communist Chinese Backed President!” as a few dozen guys in masks broke through the barricades in what started to look like an attempt at January 6 in local vernacular. Latin American history flashed before my eyes: Was this a coup? US intervention? Both? Worse? A few minutes later, it was all over. I watched the TV Azteca Twitter stream, as a breathless pseudo-journalist yelled about censorship and tyrannical repression at a woman in a wheelchair.

Like all imagery in our relentlessly spectacular political era, this content came and went. So did the invasion of Venezuela and abduction of its president. First, our reactionaries tried to exploit the attack as a win for the righteous forces of the worldwide right; but after Trump hung Corina Machado out to dry, left other Chavistas in power, and threatened the rest of the hemisphere, their praise trailed off into silence.

As a chicana I wasn’t aware of so much of this, thanks for sharing

This stuff is happening everywhere. I wasn't aware of the situation in Mexico.